|

THE

POLITICS OF ABJECTION

The

linguist, philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva,

projects a fascinating

description of the cellular transformations that provide the

very foundations of the biological processes of gestation driving

the 'biosocial history' of the maternal project. A project and a 'history'

Kristeva describes as a 'process without a subject', where the very

meaning of the concept of the 'subject' and 'identity' is brought

into question:

Cells

accumulating, dividing, fusing, splitting, multiplying and proliferating

without

any identity (biological or socio-symbolical); volumes grow,

tissues stretch,

and body fluids change rhythm, speeding up or slowing down. Master-

Mother

of instinctual drive. Material compulsion, spasm of a memory belonging

to

the species, the same continuity differentiating itself that either

binds together or

splits apart to perpetuate itself, with no other significance than

the eternal return

of the life-death biological cycle.

Kristeva appropriates and re-defines Plato's conception

of the chora, designating a site of undifferentiated being,

connoting the shared bodily space of mother and child prior to the

child's acquisition of language; and the child's sensation of continuity

or fusion with the maternal body, which is experienced as an infinite

space. In what Kristeva terms the 'semiotic', the newly-born child

possesses no sense of itself as an identity separate from its mother;

it therefore perceives no distinction between 'self' and 'other'.

Devoid of language, its existence is regulated by a rhythmic flow

of bodily desires, pulsations and bodily drives and impulses, mobile,

fluid and heterogeneous; where opposites (subject and object, male

and female, inside and outside, fascination and repulsion, life and

death) merge together into a contradictory unity: archaic and potentially

disruptive desires which are curtailed only through the arbitrary

imposition of paternal law and the 'symbolic order' of language.

For

Kristeva the maternal function subverts the traditional notion of

a fixed division between active subject and passive object. Instead,

pregnancy transforms the woman-as-subject into the passive object

or effect of a series of uncontrollable bodily processes. The biological

processes of gestation places women at the point where 'nature' intersects

with 'culture', as a sort of 'inside-out' mediator between the internal

and the external, such that the relationship between them is explained

by their reciprocal connection, their unity; a unity of the opposition

of the maternal body to itself which leads to a division of its unity

and to a splitting of its flesh. Where the mother exists as a mere

cipher or "filter" whose role is to fulfill the 'biosocial

program' of reproducing the species; where, "to imagine that there

is someone in that filter - such is the source of religious

mystifications, the font that nourishes them." The childbearing woman

is immersed in the corporeality of the maternal function, the subject

of "physiological operations

and instinctual drives dividing and multiplying her".

As

a process the woman is subjected to, the experience of gestation and

birth leads to a disintegration of the mother's self-image and symbolic

identity and a confusion and subsequent reorganisation of the boundaries

between self and other. This results in the mother internalising the

split between self and other, producing a self-division accompanied

by feelings of alienation and estrangement towards the foetus developing

within her womb, which is experienced as an 'abject' 'other' inhabiting

her body, akin to an invasive foreign organism or internal parasite:

Within the body, growing as a graft, indomitable, there is

an other. And no one

is present, within that simultaneously dual and alien space, to signify

what is

going on. 'It happens but I'm not there'".

An

internal self-contradiction finally resolved in the birth of the child

and the establishment of a maternal unity between mother and child.

A unity Kristeva pictures as an "auto-erotic circle": an imaginary

fusion of mother and child enclosed within a protective 'shell' (or

"enceinte"), where distinctions between self and other, subject and

object, are dissolved: "Narcissuslike, touching without eyes, sight

dissolving in muscles, hair, deep, smooth, peaceful colours". This

imagined unity is, however, a complex unity of opposites, a heterogeneous

and ambivalent conglomeration of experiences involving mixed emotions

associated with the processes of differentiation and separation; feelings

of love and hate, pain and pleasure, desire and fear, fulfillment

and loss: Frozen

placenta, live limb of a skeleton, monstrous graft of life on myself,

a living

dead. Life....death....undecidable....My removed marrow, which nevertheless

acts as a graft, which wounds but increases me. Paradox: deprivation

and

benefit of childbirth. But calm finally hovers over pain, over the

terror of this dried

branch that comes back to life, cut off wounded, deprived of its sparkling

bark.

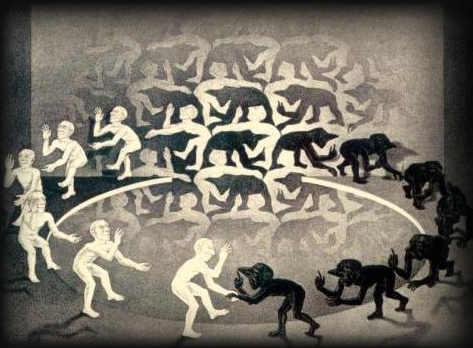

Kristeva

explores themes that connect with the

psychoanalyst Melanie Klein concerning the aggressive drives and body-destruction

phantasies of children. Thus the developing child acquires an image

of itself as an integrated 'whole', and not simply as a mess of conflicting

sensations and fragmented body parts, through a traumatic and never

fully completed process in which 'good' objects and pleasurable sensations

are incorporated into the body ('introjected'), while objects and

sensations perceived as 'bad' are expelled ('projected') out into

the external world. A process that includes aggressive phantasies

involving the murder, dismemberment and consumption of the maternal

body. Phantasies which, when projected onto the mother, create in

the mind of the infant traumatic experiences of bodily disintegration,

accompanied by the image of a hostile mother as a terrifying figure

who will eviscerate, devour and destroy it.

There

is an interesting link between these psychoanalytical theories of

bodily fragmentation and disintegration and historically archaic beliefs

concerning the deformed and the monstrous. According to the ancient

Greek natural philosopher and physician Empedokles, the evolution

of "whole-natured forms" was preceded by a lengthy period when the

earth was peopled by hybrids and mutant forms, "dream shapes" consisting

of "separate parts which were disjointed". Empedokles describes this

earlier world and its variety of polymorphously perverse forms and

monstrous combinations with a certain horrified fascination:

Many

foreheads without necks sprang up on the earth, arms wandered naked,

separated

from shoulders, and eyes wandered alone, needing brows..........and

creatures

made partly with male bodies and partly with female bodies, equipped

with

shadowy limbs.

In

paintings such as Virgin and Child with St. Anne, (1500-1510),

and Mona Lisa, (1503), the artist Leonardo Da Vinci

represents for Kristeva the identification of femininity with motherhood

and the ideal of the Virgin, where the female body is divested of

its material aspects and is transmuted through the development of

a progressively formalised set of artistic conventions and practices

into the spiritualised and reified figure of the 'phallic mother'.

The maternal (phallic body) is represented as inviolate, distinct

and whole, symbolising an established order that maintains secure

and impervious boundaries separating and distinguishing the inside

from the outside, the proper from the improper, order from chaos,

and the spiritually aesthetic or beautiful from what is deemed abject

and material.

For

Kristeva this fantasy of the phallic mother consists of an idealisation

that shields us from the threat of non-being, and the experience of

nothingness and the collapse of identity: "If, on the contrary, the

mother was not phallic, then every speaker (or 'subject') would be

lead to conceive of its Being in relation to some void, a nothingness

asymmetrically opposed to this Being, a permanent threat against,

first, its mastery, and ultimately, its stability". Kristeva thereby

concludes that the artist Leonardo Da Vinci is a dutiful "servant

of the maternal phallus", and his paintings are expressive of "the eye and hand of a child, underage to be sure, but of one

who is the universal and complex-ridden center confronting that other

function, which carries the appropriation of objects to its limit:

science ".

Kristeva

challenges the Cartesian notion of the isolated, self-contained human

being or 'ego', unmixed with others. She replaces it by the awareness

that we exist as members one of another, as a system of surfaces that

briefly intersect around a centre or constellation that dissolves,

forming parts of a 'self' conceived as a 'subject-in-process' (or

better still, as an open-ended 'work-in-progress'); a 'subject' both

constant and fluid, immersed in a continuous process of formation

and exchange, summation and integration.

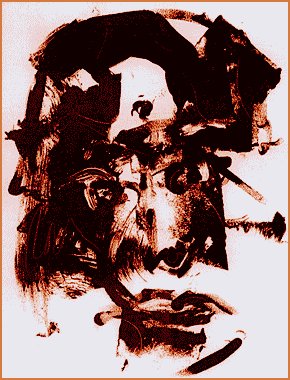

This

accords with Antonin Artaud's rigorous interrogation of the fragmented

but transforming body, in art, literature and performance –

combining chance and necessity, disintegration and reconstitution.

Artaud's body-in movement attacks stasis in favour of the transcendence

of regeneration. Painfully contorted, steeped in desire, combining,

through vocal movements and screams, violent and erotic manipulations

of the anatomy, Artaud produced in his gestural performances beautiful

images of fracture and desire. Representation is here attacked in

favour of a visceral, bodily immediacy – Artaud's Theatre of

Cruelty. The body comes before the word, and before the world:

..........

In-between

these two realms is Plato's 'Demiurgus' who creates by 'making'. A

metaphor for cosmogenesis taken from the activities of the artisan,

who shapes things from dead stuff, and not from the reproductive processes

of begetting and gestating. This concept of the cosmos as 'made' and

not 'begotten' later emerges in Christian theology as the primary

means of distinguishing between the generation of the divine in the

Trinity, and God's creation of the world. The Platonic Demiurgos first

shapes the space into the primal elements of fire, air, water, and

earth, and then shapes these into the spherical body of the cosmos.

Plato

conceptualises this sphere as a kind of living entity, without an

inside or an outside, perfectly self-contained: "Nor would there have

been use of organs by which it might receive its food or get rid of

what it had already digested, since there was nothing that went from

it or came into it". A universe, therefore, where organs of ingestion,

digestion and excretion are unnecessary, for there is nothing else

in existence, no 'other' to incorporate or excrete, nothing outside

itself it could eat even if it desired to eat, in fact, nothing it

could desire even if it desired. A perfectly self-sufficient universe

complete unto itself: "By design it was created thus, its own waste

providing its own food, and all that it did and suffered taking place

in and by itself".

Plato's

idea of the universe as some kind of living entity, is a theme taken

up by the nature philosophy of Baron Friedrich von Hardenberg (pen

name, Novalis), a leading poet and novelist of European Romanticism,

who contends that when we look at what is generally regarded as inert

matter we fall into the error that it has no consciousness at all.

But it may well be that its consciousness is so fragmented and diffused

that we can only understand it through rational systems of statistical

organisation which the study of science as hitherto revealed as the

so-called 'laws' of nature. This means that in the human knowledge

of nature, nature perceives itself; and that the subject-object (male/female)

relationship to nature is in fact nature's relationship to itself.

A complex relationship indeed, where, to quote Novalis, "the organs

of thought are the sexual organs of nature, the world's genitals".

A conception of nature that the inveterate anti-Platonist Friedrich

Nietzsche reacted to with disgust and revulsion: "The modern scientific

pendant to a belief in God is the belief in the universe as organism:

such belief makes me want to throw up".

Novalis

continues: for him the process of self-knowledge is a natural and

universal drive towards expansion and fulfillment, where the urge

to know is identical with the urge to appropriate and ingest, where

differences and distinctions are abolished, and the 'other' becomes

the same as 'oneself': "How can a human being have a sensibility for

something if he does not have the germ of it in himself? What I am

to understand must develop organically in me; and what I seem to learn

is but nourishment - something to incite the organism. Thus learning

is quite similar to eating".

For

Novalis the act of philosophising culminates in the 'kiss', an act

symbolising the unity of subject and object. "Life, or the essence

of spirit, thus consists in the engendering bearing and rearing of

one's like. The human being engages in a happy marriage with itself,

an act of self-embrace". Like the myth of the youth Narcissus, hopelessly

in love and unwilling to separate himself from the beauty of his face

reflected in a pool of water, his body gradually fading away, to be

replaced by a flower. A jouissance involving a blissful acceptance

of life's transience, and a willing immersion into the chaos of unformed

matter into one all-encompassing unity. Leading to a pantheism like

that of the heretic and philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who rejects the

philosophical dualism and the principles of transcendence and sublimation

of the established Christian order in favour of a God who is the immanent

cause of all existence, where everything is considered alive and all

things in the world are one, and what's in all things is God. A mystical

and pantheistic view of Nature, an oceanic feeling of 'oneness with

the universe', which, according to Freud, amounts to the restoration

of an archaic infantile state of limitless narcissism, a condition

articulated poetically by the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who describes

the world as "an immense Narcissus in the act of thinking about himself.".

In

accordance with Kristeva's re-mix of themes and stanzas sampled from

the Romanticism of Novalis, 'love', or the desire that is expressed

in song, in the disposition to rhythm and intonation

"makes individualities communicable and comprehensible"; makes

nonsense abound with sense: makes (one) laugh. For Kristeva "The amorous

and artistic experiences are the only ways of preserving our psychic

space as a 'living system'" 'opening' up the individual's psyche to the point where the

outside world of the other is no longer perceived as a threat but

instead becomes a stimulus to adaptation, change and self-transformation,

revealing the participating 'subject' as "a work in progress capable

of auto-organisation on condition of maintaining a kind of link with

the other. I have called this the amorous state".

To

rediscover the intonations, the lyrical patterns, repetitions, and

rhythms preceding the subject's establishment within the paternal

(symbolic) order of language is to discover the voiced breath that

fastens us to an undifferentiated mother, a semiotic motility, a playful

polyvalence, released and restructured in the poetry of art. The discovery-in-utterance

is also at the same time an act of losing, of distancing, of separating

oneself from what has been discovered; it is an act of unknowing,

a dissolution back into an active potential. The potentiality of the

fragmented unity of the symbolic revitalised by energies borrowed

from the prehistoric and archaic realms of the semiotic; a disruptive

negativity involving a dialectical tension between dispersal and unity,

rupture and completion, producing a 'fluid subjectivity. A 'subjectivity'

of 'difference' where continuity is achieved

through an ongoing process

of transformation.

Accordingly,

it is not the possession of a fixed 'truth' so much as the realisation

of the 'known' so that it becomes the 'given', thereby not arresting

reflection, but renewing and stimulating it. Novalis compares it to

the ignition of a flame, a leaping outside oneself in desire and ecstasy:

"The act of leaping outside oneself is everywhere the supreme act

- the primal point - the genesis of life. Thus the flame is nothing

other than such an act. Philosophy arises whenever the one philosophizing

philosophizes himself, that is, simultaneously consumes (determines,

necessitates) and renews again (does not determine, liberates). The

history of this process is philosophy".

According

to Kristeva, we attempt to prevent the disruption and destabilisation

of the socially determined and 'ideological' belief that we exist

as unchanging subjects with fixed identities within an organised and

static social order, by denying and excluding as unclean and disgusting

anything that reminds us of our (material) corporeal natures. This

dual process of denial (repression) and exclusion (projection) is,

however, only ever partially successful. The presignifying traces

of the chora: the maternal, corporeal desires that underlie

the socio-symbolic order of signification, are forever irrupting as

emotional affects, permanently threatening to destabilise the finite

unity and autonomous, fixed, and singular identity of the 'ego' or

'subject'.

For

Kristeva the whole affair revolves around the establishment of a series

of demarcations and dichotomies between an "inside-outside", a "me-not

me", and a "'not-yet me' with an 'object'". A theme initially explored

by the Kleinian school of psychoanalysis:

Owing

to these mechanisms (of introjection and projection) the infant's

object can

be defined as what is inside or outside his own body, but even while

outside, it

is still part of himself, since 'outside' results from being ejected,

'spat out': thus the

body boundaries are blurred. This might also be put the other way

round: because

the object outside the body is 'spat out', and still relates to the

infant's body,

there is no sharp distinction between his body and what is outside.

This

brings into question the whole Cartesian 'inside' and 'outside' dichotomy.

The cohesion and unity of the 'subject' or 'ego' is based upon its

ability to distinguish itself from those objects that lie outside

it. The ego's relationship to the outside world is explained by psychoanalysis

through the processes of 'projection' and 'introjection'; processes that create the

distinction between the internality of the 'ego' or 'subject' and

the 'externality' of 'objects' residing in the world 'outside'. For

both introjection and projection are mutually interdependent, one

upon the other, both inside and outside each other at the same time;

thus the inside is also on the outside, while the outside is both

inside and outside too. The ego wants to 'introject', to bring 'inside'

only that part of the external world with which it can identify. However,

this very identification of the subject with these external objects

puts the absolute externality of these objects in doubt. The question

therefore arises: is it a part of the outside world that the subject

wishes to introject, or is it merely a part of the subject itself;

a part, moreover, which has to be 'projected' and externalised into

the world 'outside' before it can be introjected 'inside'? A question

(and a potential antagonism) first expressed in the language of the

"oldest" instinctual drives - the oral - through the contrast between

incorporation (eating) and expulsion.

Accordingly

the 'ego' introjects and incorporates into itself everything that

is 'good', and ejects from itself everything that is 'bad'. The boundary

between subject (ego) and object (external world) is, however, somewhat

paradoxical: the 'outside' is forged and maintained at the heart of

the 'inside', and is kept 'outside' by the very living organism from

which it is supposed to be separated. The limits of the ego's boundaries

thus resembles a form similar to that of the mouth. Like the mouth

(which is also a point of incorporation

or 'taking in'), the ego's 'boundary' is not just a system of surfaces

that divides inside from outside; it is also and equally a meeting

of surfaces, a permeable interface, amounting to a blurring of boundaries.

For

Kristeva, therefore, the mouth is both a place of entry and exit,

one of the body's orifices that connects inside with outside, forming

a vulnerable corporeal boundary or threshold that can easily be trespassed.

The mouth can eat, kiss, suck, emit sounds, and produce language.

In addition, cultures and religions elaborate complex taboos concerning

food designated as 'unclean', setting the boundaries between what

may or may not be legitimately consumed. According to Kristeva, "food

is the oral object (the abject) that sets up archaic relationships

between the human being and its other, its mother who wields a power

as vital as it is fierce". A complex borderline between self and other,

initially permeable, like the embryo in the womb, and, after birth,

as the infant sustained by milk from its mother's breasts. However,

in the process of accepting the gift of milk, we confront the realisation

that we exist as the separate objects of our mother's desire. The

infant's refusal to separate is expressed as physical nausea. This

sensation of nausea not only exposes the complex relationship of sameness

and difference between our mothers and ourselves, but also reveals

the threat posed by the maternal space as the final collapse of distinctions

between subject and object; the loss of identity and of an integrated

sense of 'self ' which the contained body represents; and a slippage

between opposites, suggesting an indivisibility of erotic attraction

and repulsion which are held apart within the conventional binary

division of sexual difference.

Like

an hermaphrodite who combines the two sexes in one body (in accordance

with Artaud's biography of the third-century transgendered Roman Emperor,

Heliogabalus) a potential bisexuality of desires in which self and

other cannot be fully separated. For Kristeva, "To believe that one

'is a woman' is almost as absurd and obscurantist as to believe that

one 'is a man'". It is not the sexual difference between subjects

that is important, so much as the sexual differentiation within each

subject. The bisexual constitution of the child, the presence of masculinity

and femininity within the same body, informs her view. The anorexic's

refusal to eat can be explained as a desperate attempt to maintain

the boundaries separating subject and object, reminding us of the

bone beneath the skin, our mortality, and the materiality that necessitates

our decay, while simultaneously expressing the attempt of an irrevocably

divided subject to become united with itself; where the wholeness

and integrity of the human body and of the unitary 'subject' is equated

with holiness, and connected to the being and goodness of God - the

Ideal: "To be holy is to be whole, to be one; holiness is unity, integrity,

perfection of the individual. Dietary rules and prohibitions merely

develop the metaphor of holiness".

Eating

dissolves the boundaries separating the self from the world, a process

described by the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his

meditation on the mystery of the Eucharist: "Yet the love made objective,

this subjective element becomes a thing, and only reverts once

more to its nature, becoming subjective again in eating". Hegel describes

his philosophy as "a circle returning upon itself, the end being wound

into the beginning, a circle of circles", culminating in "the crowning

glory of a spiritual world", the Absolute Idea, where spirit is reality

and reality is spiritual. For Hegel the identification of the object

with itself can be thought of as a unity of the opposition of the

object to itself up to and including identity which leads to a splitting

of its unity.

This

dialectical notion of the self-motion of the object takes the form

of an impulse, a vital tension, or, to borrow a term used by the medieval

mystic Jakob Bohme, a 'qual' of matter. 'Qual' meaning an internalised

pain or torture, an agony issuing from within; a quality Bohme considers

as intrinsic to all material substance, which drives to action of

some kind; an activating principle, arising from, and promoting in

its turn, the self-movement and spontaneous development of a thing,

in contradistinction to the development or movement of a thing derived

from a pain or pressure inflicted from without. This dialectical notion

of the self-motion of the object includes an identity of the object

with itself such that the object is and is not, at one and the same

time, and in one and the same relation, in one and the same state,

which leads ultimately, by virtue of the internal dynamic of its 'qual'

or agony, to its transformation into another object. The contradictoriness

of this self-transformation of the self-moving object is logically

overcome by admitting of the possibility of relating the self-moving

object with itself as with 'its other', which appears as the identity

of equal quantities, but of opposite sign.

For

Julia Kristeva an androgyny or bisexuality seen as the traversing

or transgression of boundaries, where the 'subject' no longer experiences

sexual difference in 'essentialist' terms as a fixed opposition between

'man' and 'woman', but as a liberating process of sexual differentiation

amounting to a perpetual alternation and confusion of 'subject-positions',

eluding the totalising grasp, or the Aufhebung of the philosopher

Hegel, which expresses his desire for a final resolution or synthesis

of the opposed terms; where spirit unites with nature and indeed becomes

its master because nature turns out to belong to spirit, to be nothing

other than spirit, where, as Hegel writes, "nature is the bride which

spirit marries". A reunion of opposites essentially identical, just

like the marriage of Adam and Eve.

By

rejecting the invasion of the body by external matter, and avoiding

the consumption of food as an external 'pollutant', the anorexic -

like a true philosophical idealist! - aspires to escape from the confused,

mutable and brutish world of materiality towards a stabilised unity

of identity, the Good and the Perfect, the Absolute Idea or Universal

Subject, which is God: disembodied thought thinking itself. For the

anorexic, therefore, "The ultimate self-abjective wish becomes the

desire to completely eliminate 'flesh', to become 'pure'".

As

an alternative to the transcendental ego of the Hegelian spirit, Kristeva

opts for a disordered and lyrical 'subject-in-process'. This amounts

to a dislocation of historical syntax such that history is experienced

not as a narrative progression and sequential unfolding of a

story-line or 'plot', in accordance with Hegelian notions of

'historical development' and inevitable 'progression' towards some

climactic conclusion or final synthesis, but is instead pictured as

a rhythmic drive that disrupts, opposes and threatens meaning and

social order. A drive that destabilises the fixity and allocated subject-positions

of the speaking 'I' or unitary 'subject', towards a more primitive

and dynamic aggregation of pleasurable and erotic bodily sensations.

A process of perpetual negation involving continual irruptions of

powerful semiotic pulsations and drives, with the potential to break

up the inertia and calcified

rigidities (character armour) of routine behaviour patterns and the

sclerotic deposits (cliches) of language habits, thus presenting a

threat to such fixed signs of the symbolic order as paternal authority,

the state, the family, private property, and propriety.

The

polymorphously perverse desires and pulsating drives of the semiotic

body are revealed in rhythmic flows, intonations, repetitions, and

psychotic babble; where distinctions between reality and fantasy,

male and female, 'self' and 'other', the psychological and the somatic,

the 'subject' and the processes of history, are mixed and

juxtaposed; like a poetic text where rupture and discontinuity

predominate, and fragmentation replaces cohesion. A condition resolving

itself in an 'impossible dialectic': a transgression and dissolution

of boundaries; a hybridity and an androgyny, simultaneously enacting

socially prohibited impulses while demanding their 'symbolic' repression,

containment, ordered articulation and enunciation, in the organised

form of a speaking 'subject'. A process culminating in the necessary

curtailment and organised 'symbolic' articulation, codification and

recuperation of an ambivalent and provisional 'unity' of opposed desires:

"(appropriation/rejection, orality/anality, love/hate, life/death)".

A condition described by Kristeva in the following terms: "She was

a man; she was a woman.......It was a most bewildering and whirligig

state to be in".

The

'abject' is a term employed by Kristeva to refer to a class of unspeakable

phenomena excluded from our sense of social order,

something that "disturbs identities, systems, orders. Something that

doesn't respect limits, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous,

the mixed". The 'abject' also includes whatever reminds us of our

material natures, threatening to disrupt the notion of ourselves as

individual subjects, with secure borders and an unchanging essence

or inner 'core' of identity, unified and in command of ourselves and

our environment. For Kristeva abjection is a complex mixture of yearning

and condemnation, the proper and the improper, order and chaos, preserving

"what existed in the archaism of pre-objectal relationship, in the

immemorial violence with which the body becomes separated from another

body in order to be".

Human

beings therefore repress that which reminds them of their corporeality

by categorising it as unclean and disgusting. This attempt at exclusion

can only ever be partially successful. At moments when we are forced

to recognise this, the reaction is one of extreme repulsion - what

Kristeva calls an 'act of abjection'. Dirt, disorder and formlessness

pose a threat to the body and its boundaries, in the form of a vital

distinction between the inside of the body and its outside, the self

from the space of the other. In other words, the fixing of limits

and boundaries is bound up with the construction of the individual

subject as a unified self, with a central 'core' of identity unique

to each individual. Conceptualised as wanton materiality, the female

body is perceived as a potential threat to this order, lacking containment

and issuing filth and corruption from permeable boundaries, porous

surfaces and indefinite outlines:

Any

structure of ideas is vulnerable at its margins. We should expect

the orifices of

the body to symbolise its specially vulnerable points. Matter issuing

from them is

marginal stuff of the most obvious kind. Spittle, blood, milk, urine,

faeces or tears

by simply issuing forth have traversed the boundary of the body.

In

addition, Kristeva describes the abject as possessing the qualities

of Otherness, and the ambivalence of horror and desire. The abject

is a polluting agent, defined against the boundaries it threatens.

Excluded as unclean and improper from the logical and social order

of the 'symbolic', its psychic structure can be traced, according

to Kristeva, to a primary narcissism ; a narcissism laden with an

hostility without limits, where the instincts of life and death merge

together into a "violence of mourning for an 'object' that has always

already been lost".

The

lost object is the mother, and the unfulfilled desire for her is laden

with unacceptable wishes of forbidden (polymorphously perverse) pleasures

and drives (love/hate, life/death) that need to be sublimated. Like

a taboo it is born out of primal repression which designates and excludes

the mother's body as the non-object (or 'abject-object') of desire.

According to Kristeva, this primal repression, which is pre-verbal

(unspeakable), is displaced through a process of denial onto another

object, a metaphor, through signification, symbolisation and sublimation

(including fetishism and phobia). Thus the psychic and social mechanisms

of displacing the abject are a transformation of the impossible object

into a fantasy of desire, where the unspeakable is uttered through

rhythm and song and the sublimation of artistic reproduction.

According

to Kristeva "the existence of psychoanalysis reveals the permanence,

the ineluctability of crisis" of

"The speaking being (who) is a wounded being, with its discourse

dumb from the disorder of love, and the 'death drive' (Freud) coextensive

with humanity". In Beyond The Pleasure Principle, Sigmund Freud

describes the death drive as "the most universal endeavour of all

living substance - namely to return to the quiescence of the inorganic

world". Like a river winding its way back to the sea, life is but

a series of "complicated detours" or "circuitous paths to death".

Freud's illustrations of this drive include the "momentary extinction"

of orgasm, and a story of origins derived from "the poet-philosopher"

Plato: "the hypothesis that living substance at the time of its coming

to life was torn apart into small particles, which have ever since

endeavoured to reunite through the sexual instincts".

The

speculations of Freud on the nature of living substance at the time

of its coming into being bears a resemblance to the theories of the

biochemist Lynn Margulis on the origin of nucleated cells. According

to Margulis, for millions of years before cells with nuclei appeared,

living prokaryotes (cells without nuclei) dominated the Earth. Margulis

contends that nucleated cells originated when non-nucleated bacteria

devoured one another. Some of the bacteria that were eaten were not

digested or destroyed, but somehow managed to survive and adapt to

live inside their host predator cells as symbiotic organelles: little

organs. Cells within cells utterly interdependent (endosymbiotic),

forming stable, compound organisms - new wholes far greater than the

sum of their parts. These compound organisms gradually evolved into

fully fledged eukaryotes - living cells that possess a central nucleus

suspended in cytoplasm: the whole wrapped in a cell wall, like the

yolk of an egg surrounded by a protein sac, safely enveloped within

a protective shell (an 'enceinte'). For Margulis, multicellular organisms

such as ourselves are coordinated collective composites or colonies

of cells, and each individual cell is likewise a composite of cooperating

micro-organisms.

Margulis'

theories intersect with Freud's own speculations about the history

of living substance, with the added twist that for Freud this substance

was originally a unity that has somehow been torn apart and is forever

striving towards regaining this long lost unity in the form of an

ever more complex "combination of the particles into which living

substance is dispersed". Freud marvels at the seemingly insurmountable

difficulties encountered by these early unicellular organisms - "splintered

fragments of living substance" - in their first attempts at reuniting

as multicellular entities, and the necessity "which compelled them

to form a protective cortical layer.......by an environment charged

with dangerous stimuli". For Freud it would appear that the colonies

of cells that make up the multicellular organism collectively constitute

a defence mechanism against a hostile external environment.

Then

there is Freud's equation of life and death, the animate and the inanimate:

"the hypothesis of a death instinct, the task of which is to lead

organic life back into the inanimate state". Perhaps this final state

of entropic dissolution and restful oblivion is a return to the unity

originally lost. Freud's answer to the question of life's purpose

and direction appears endlessly circular, a ceaseless ebb and flow

- "But here, I think, the moment has come for breaking off". For

Artaud the term 'cruelty' encapsulates the tight rapport between life

and death:

Above all, cruelty is lucid, it is a kind of rigid direction,

submission to

necessity. No cruelty without consciousness, without a kind

of applied

consciousness. It is consciousness which gives to the exercise

of every action

in life its colour of

blood, its cruel touch, since it must be understood that to

live is always through the death of someone else.

The

process "which makes mammiferous larvae into human children, masculine

or feminine subjects" begins with the body of the newly-born

infant, which is a seething mass of excitations, impulses and instinctual

drives; a disorganised bundle of parts and sensations (the body 'in

bits and pieces'), completely lacking in any sense of itself as a

coherent, unified entity. Freud terms this the 'primary narcissistic'

or 'polymorphously perverse' stage of infantile development: a stage

with no sense of 'self', centring or organisation, where the desiring

sensations ('libido') are diffused throughout the entire body, internally

and upon the skin's surface. A strange blend of self-sufficiency on

the one hand, mobility and dispersion on the other.

Gradually

the infant begins to view itself as a coherent, unified being, distinct

from its mother and its environment. This awareness of the difference

between the self and the rest of the world is the foundation upon

which the infant begins to acquire language. Language provides the

infant with a means of articulating reality in a way that seems to

realise its struggle for reintegration as a coherent subject. For

Kristeva, however, both the infant's and adult's idealised representation

of themselves as autonomous, whole beings is an illusion. The 'self'

or 'ego' is 'in reality' fragmented and disjointed; and the sense

of completeness, wholeness, and oneness characteristic of the imaginary,

ideal self which we identify with and seek, exists as an unattainable

fiction.

For

Kristeva cultural production is implicated in an ideological process

of constituting undivided subjects - in conformity with the controlling

ego of traditional Western philosophy (a view enunciated by the philosopher

Rene Descartes, who declares: '(I) think therefore (I) am'). The fractured,

multifaceted, fragmentary and contradictory nature of the self is

denied, and anything that threatens the illusory integrity of the

ego and its borders is ruthlessly excluded as 'abject'. The classic

realist text or painting plays its part in constituting the subject

by inscribing the viewer or reader within the work itself, providing

a place for the viewer or reader to occupy if 'he' or 'she' is to

enter this ideal fiction of an integrated subject, and be entertained,

basking in the illusion of possessing secure boundaries and a stable,

fixed 'subject-position' (and sense of 'self').

If

the classic realist text provides the reader with the illusion of

stable boundaries and a fixed subjectivity and identity, for Kristeva

the 'revolutionary' ('avant-garde') art of the late nineteenth and

twentieth centuries exploited the semiotic dimension of what Kristeva

calls the signifying process. Mallarme, Joyce, and Artaud have shaken

the existing configuration of the symbolic and given rise, in Kristeva's

interpretation, to a theory of the subject in process: a subject equally

constituted by symbolic and semiotic elements. The resulting subject

exists as a rhythmic reverberation in the symbolic, a reverberation

that connotes both union with, and separation from, the mother. According

to Kristeva:

Artaud

interrogated the established institutions in order to have done with

language

and the unity of consciousness. He set up this tug of war with possibility,

where

on the one hand there was the possibility of speaking to people who

came to hear

him or of writing books, and on the other hand there was the experience

of non-sense,

for example in the texts composed of glossololalia which mean nothing

and are totally

explosive, which are no longer language but pure drive. So it was

this kind of

balancing act that he was trying to sustain with regard to values

– whilst exposing

himself in an immense rage against others and himself – that

I was examining and

was attempting to go along with.

The

notion of the infant's body as fragmented and fluid (the body 'in

bits and pieces') corresponds to the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan's

'pre-mirror' stage. For Lacan, the newly-born infant is not yet a

complete human being: physiologically the nervous system is not yet

fully formed, and socially language is still to be acquired. The infant

is unable to differentiate itself from its mother or its surrounding

environment. A condition described by Freud as resolving itself through

a process whereby the child's disorganised desiring sensations gradually

coalesce and become focussed on the mouth as the first in a developmental

succession of organs of pleasure ('erogenous zones'). For it is through

the mouth that the child makes contact with the principle object of

desire - the mother's breast.

To

the newly-born infant, the outer world with its infinite stimuli is

chaotic, a chaos from which the sensations from its own body are a

part. Ego and outer world, self and other, are experienced as a unity.

All that is pleasurable belongs to an expanded ego, "which absorbs

into identity with itself the sources of its pleasure, its world,

its mother" With time, this changes. Sensations belonging to the outer

world are recognised as internal to the body, while parts of the outer

world which are pleasurable, such as the maternal nipple, are recognised

as belonging to the world outside. In this way, a unified ego gradually

crystallises from the primordial chaos of internal and external perceptions,

and establishes boundaries separating itself from an outside reality.

The ego thus becomes "a shrunken vestige of a far more extensive (oceanic)

feeling - a feeling which embraced the universe and expressed an inseparable

connection of the ego with the external world".

Freud's

pre-Oedipal stage of the self-absorbed, narcissistic infant and Lacan's

notion of the 'pre-mirror' stage share in common an understanding

of the similarity between the infant's and the adult schizophrenic's

manner of experiencing the world. Both experience a harmony without

any boundary between ego ('self' or 'subject') and the outer world

of 'external' 'objects'.

The

onset of Jacques Lacan's 'mirror stage' marks the illusory and complex

development of a separate ego formed as part of a narcissistic relationship

between self and other, and the division of an androgynous whole into

two symmetrical male and female images; torn halves that gaze longingly

at each other across an abyss of difference that both joins and separates.

Lacan uses the term 'imaginary' to denote the way in which the subject

is seduced by this image of otherness (initially the mirror reflection

of the body) and takes this image as a representation of the 'self'.

In the mirror stage, the human being attempts to coordinate an amalgam

of sensory and motor reflexes and responses via the establishment

of a fixed and rigid 'Ideal-I', consisting of an imaginary, ideal

image with which he or she will never coincide, and an 'I' that can

never be realised. This ideal domain of the self-contained ego belongs

to the symbolic order of language, of the Name-of-the-Father, of castration

and the unconscious (an internalised authority Lacan describes as

the 'ideal incubus').

Lacan

contends that at the heart of the ego lies a complete void: "The ego

is constructed like an onion, one could peel it, and discover the

successive identifications which have constituted it". An inexhaustible

search comparable to the endless labour of 'laying bare', 'extracting'

and 'refining', involved in the process of revealing that seemingly

elusive 'rational kernel' concealed somewhere beneath the superimposed

skins - "of a certain crust which is more or less thick (think of

a fruit, an onion, or even an artichoke)" - constituting the external, 'mystical shell' of Hegel's philosophy

of the Absolute Idea. Referring to Hegel's system, Lacan concludes:

"when one is made into two, there is no going back on it. It can never

revert to making one again, not even a new one. The Aufhebung

(sublation) is one of those sweet dreams of philosophy".

Freud

discusses the formation of a bounded sense of self, of the 'ego',

and the separation of the ego (subject) from the external world (object)

as a process whereby:

objects

presenting themselves, in so far as they are sources of pleasure,

are absorbed by the ego into itself,

'introjected'...........while, on the other hand the

ego thrusts forth upon the external world whatever within itself gives

rise to

pain (the mechanism of projection).

According

to Lacan, prior to the onset of the 'mirror stage', the child is completely

devoid of any sense of itself as a 'unity', and lacks a fixed sense

of itself as possessing a coherent 'identity' separate from whatever

is 'other' or external to it. A transformation takes place however

with the arrival of the mirror stage, when the child, like the legendary

Narcissus, falls in love with the reflected image of itself, and identifies

with this illusory 'other' as an ideal image of wholeness and 'subjecthood'.

Lacan describes the mirror stage as the ineluctable unfolding of a

drama:

The

mirror stage is a drama whose internal thrust is precipitated

from insufficiency

to anticipation - which manufactures for the subject, caught up in

the

lure of spatial identification, the succession of phantasies that

extends from a

fragmented

body-image, manifested in dreams as the individual's aggressive disintegration,

in the form of disjointed limbs, or of those organs represented in

exoscopy, growing wings and taking up arms for intestinal persecutions

- the very

same that the visionary Hieronymous Bosch has fixed, for all

time, in painting, in

their ascent from the fifteenth century to the imaginary zenith

of modern man.

A

drama that commences with the infant's emergence from an undifferentiated

state of insufficiency (a body in bits and pieces) into an orthopedic

'form' which is then 'finalised' in the fixed position of a unitary

'subject' in conjunction with the formation of a protective armour:

the isolating "armour of an alienating identity, which will mark with

its rigid structure the subject's entire mental development". The

armour of an alienating identity that compares with the carapaces

of insects and the rigid, undifferentiated, automatic (and 'unfeeling')

nature of their stimulus and response motor reactions towards the

pressure of instinctual drives triggered by external events. For example,

the 'ichneumonid wasp' (a group of several hundred related species

of wasps) seeks out and encounters either a cricket or a caterpillar,

paralyses the 'host' insect with its sting, and then inserts its eggs

into the host's body. When the larvae hatch they eat the living, paralysed

body of the host from the inside out -

carefully avoiding the vital organs in order to extend the

life (and agony) of the host for as long as possible lest its body

decay prematurely, spoiling the meat .The entomologist William Kirby

esteems the ichneumonid wasp most highly for its judicious husbanding

of its economic resources:

In this strange and apparently cruel operation one circumstance

is truly

remarkable. The larva of the Ichneumon, though every day, perhaps

for

months, it gnaws the inside of the caterpillar, and though

at last it has

devoured almost every part of it except the skin and intestines,

carefully

all this time it avoids injuring the vital organs, as if aware

that its own

existence depends on that of the insect upon which it preys!

With

equal respect, the entomologist J. M. Fabre describes with horrified

fascination and in meticulous detail how the lava of the Ichneumon

dictate the movements of its cricket host:

One may see the cricket, bitten to the quick, vainly move its

antennae and

abdominal styles, open and close its empty jaws, and even move

a foot, but

the lava is safe and searches its vitals with impunity. What

an awful

nightmare for the paralyzed cricket!

The

ability and the calculated precision of the Ichneumon is not acquired

through practice - it is an inflexible 'instinctual' response to external

stimuli, a biological quality inherent in the wasp. As a matter of

fact we know that the outstanding difference between human beings

and their fellow animals consists in the infantile morphological characteristics

of human beings, in the prolongation of their infancy. This prolonged

infancy allows for a certain plasticity whereby the rigid motor responses

of instinctual behaviour are superseded by the transmission of culture

and the capacity to 'learn', adapt to and modify the external environment.

This explains the traumatic character of sexual experiences not shared

by our animal brethren and the existence of the Oedipus Complex itself

which is a conflict between the instinctual drives of the Id and the

demands of cultural adaptation, expressed as an internalised conflict

between archaic and recent love objects. Finally the defence mechanisms

themselves owe their existence to the fact that the human 'Ego' is

even more retarded than the instinctual 'Id' and hence the immature

'Self' or 'Ego' evolves defence mechanisms as a protection against

libidinal quantities which it is not prepared to deal with:

In man, however, this relation to nature is altered by a certain

de-hiscence

at the heart of the organism, a primordial Discord betrayed

by the signs of

uneasiness and motor unco-ordination of the neo-natal months.

The

objective notion of the anatomical incompleteness of the pyramidal

system and

likewise the presence of certain humoral residues of the maternal

organism confirm the view I have formulated as the fact of

a real specific

prematurity of birth in man.

It is worth noting, incidentally, that this is a fact recognized

as such by

embryologists, by the term foetalization, which determines

the prevalence

of the so-called superior apparatus of the neurax, and especially

of the

cortex, which psycho-surgical operations lead us to regard

as the intra-

organic mirror.

The theory of retardation is also put forward from another point of view by Robert Briffault:

It

has been seen that the power of nutrition and of reproduction decrease

in the cell in proportion to the degree of fixation of its

reactions, that is, in

proportion to its differentiation and specialization.....The

higher the degree

of specialized organization and differentiation which the cells

of the

developing being have to attain, the slower the rate of growth.

Hence it is

that the higher we proceed in the scale of mammalian evolution,

the longer

is the time devoted to gestation.

Even more important is the fact that, although the time of

gestation is

thus lengthened, the rate of individual development becomes

slower as

we rise in the scale of organization and the young are brought

into the

world in a condition of greater immaturity. Infantile

or fetal characteristics which are temporary in other animals therefore

seem to have become stabilised in the human species. In Race, Sex

and Environment, Marett makes bold as to speculate that the causes

of human retardation can be traced back through psychology and the

endocrine system to minerals available in the soil. According to Marett,

"Lack of any structural material would seem in the long run likely

also to result in a slow rate of growth". "Lime deficiency is thus

thought to encourage femininity, and iodine shortage to favour fetalization.

Yet since many of the aspects of youth and femininity are similar,

it will not be easy to distinguish between the two possible causes

of a similar state". Regardless of the validity of these conjectures,

fetalisation or paedomorphosis are generally acknowledged

as one of the processes whereby human characteristics have emerged

in evolution. The

structural anthropology of Claude

Levi-Strauss focuses on the analysis of the 'synchronic' structures

characteristic of 'cold' or 'primitive' societies designated as timeless

and static, and permanently stabilised in the reproduction of one

and the same cycle. In contrast, the 'diachronic' sequences of 'hot'

or 'advanced' societies considered as evolving 'in history', involving

processes of movement and change, seem to elude the grasp of Levi-Strauss'

structural analysis. It appears that events already frozen in the

historical past survive in our consciousness only as myth, for it

is an intrinsic characteristic of myth (as it is also of Levi Strauss' system of structural analysis)

that the chronological ('diachronic') sequence of events is irrelevant.

The analysis of structures is strictly designed to determine how relations

which exist in Nature (and are apprehended as such by human brains)

are used to generate cultural products which incorporate these same

relations. Against the philosophical 'idealists' who contend that

Nature has no existence other than its apprehension by human minds,

Levi-Strauss' approach is 'materialist': Nature is for him a genuine

reality 'out there'. A Nature governed by natural laws which are accessible,

at least in part, to human scientific investigation. But our capacity

to apprehend the nature of Nature is severely restricted by the nature

of the apparatus (the human brain) through which we do the apprehending.

The structural analysis of 'primitive' myth, by carefully examining

the classifications and resulting categories used in the processes

of apprehending Nature, attempts to gain an insight into the workings

of the 'universal' codes and structures that govern the mechanisms

of our thinking.

On

the face of it, Levi-Strauss' notion of a fundamental divide between

'myth' (the synchronic) and 'history' (the diachronic) seems to share

an affinity with Julia Kristeva's perspective on the division between

the cyclic or monumental time of motherhood and reproduction, and

the linear, historical time of production and the symbolic discourse

of language, considered as the enunciation of an ordered sequence

of words. However, Kristeva transforms this division into a complex

dialectical relationship and reciprocal interaction between a polymorphously

perverse and chaotic semiotic realm, "detected genetically in the

first echolalias of infants as rhythms and intonations" and the symbolic

order and fixity of the speaking subject.

A

division that compares with the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's

duality of the Dionysian element of raw chaotic sensual power versus

the balanced order and organisation of the Apollonian aesthetic (and

the synthesis of the Dionysian with the Apollonian in the culture of the ancient

Greeks), or the philosopher Henri Bergson's duality of the spontaneous

and creative flow of interpenetrating qualities which he terms 'duration',

in opposition to the 'geometric' order of well-defined elements organised

in accordance with definite rules. For Leon Trotsky the powerful flow

is by its very nature a primordial rawness prior to any organised

structure. Moreover, it expresses a protest against artificiality,

a move away from the static rigidities and impositions of an outworn

established order: "While in our uncouth Russia there is much barbarism,

almost zoologism, in the old bourgeois cultures of the West there

are horrible encrustations of fossilized narrow-mindedness, crystallized

cruelty, polished cynicism".

In

accordance with this view, civilisation establishes an elaborate code

of distinctions, and these distinctions govern everything. As distinctions

exhaust their power to distinguish, new ones are employed. The tendency

is toward finer and finer discrimination and increasing attention

to detail, to the point of decadence. A view taken up by Roland Barthes

who contends that 'myth', like a parasite, saps the living energy

of history:

For

the very end of myths is to immobilise the world: they must suggest

and mimic

a universal order which has fixated once and for all a hierarchy of

possessions.

Thus, every day and everywhere, man is stopped by myths, referred

by

them to this motionless prototype which lives in his place, and stifles

him in the

manner of a huge internal parasite assigning to his activity the narrow

limits within

which he is allowed to suffer without upsetting the world.

The

civilising process is directed towards self-restraint, as Norbert

Elias so clearly shows. The ways in which this restraint is marked

- the specific forms, details, and nuances - give class culture its

distinctive flavour at each point in history. Habituated and internalised,

the emotional economy of social nicety creates thresholds of embarrassment

that shift. Practices once considered perfectly acceptable, such as

wiping the hands on the table cloth, are later experienced as disgusting.

Nowhere is taste so vividly inscribed as on the body, which the good

manners of polite society so systematically denies. The body in good

taste is conceived as self-contained, whole and complete (or is discreetly

altered to appear so). It derives from the values propagated by the

European Enlightenment - reason, moderation, classical formality,

individual autonomy, and monadic self-sufficiency. But there is also

a grotesque body, which, according to Kristeva's study of Mikhail

Bakhtin's work on the writings of Francois Rabelais, is "not a closed completed

unit; it is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits.

The stress is laid on those parts through which the world enters the

body or emerges from it, or through which the body itself goes out

to meet the world. This means that the emphasis is on the apertures

or the convexities, or on the various ramifications and offshoots:

the open mouth, the genital organs, the breasts, the phallus, the

potbelly, the nose". And it is the image of the prominent Jewish nose

that the critical theorist Theodor Adorno considers as a focal point

of difference contributing to the virulent hatred of the anti-Semite.

The despised prominence of the persecuted Jew's nose is described

by Adorno as: the

physiognomic principium individuationis, symbol of the specific

character of an

individual, described between the lines of his countenance. The multifarious

nuances

of the sense of smell embody the archetypal longing for the lower

forms of existence, for direct

unification with circumambient nature, with the earth and mud.

Of all the senses, that of smell bears closest witness to lose oneself

in and become

the 'other'. When we see we remain what we are; but when we smell

we are

taken over by otherness. The trend to lose oneself in the environment

instead of

playing an active role in it; the tendency to let oneself go and sink

back into nature.

Freud called it the death instinct, Roger Caillois 'le mimetisme'.

This urge underlies

everything which runs counter to bold progress, from the crime which

is a

shortcut avoiding the normal forms of activity, to the sublime work

of art. A yielding

attitude to things, without which art cannot exist, is not so very

remote from

the violence of the criminal. Hence the sense of smell is considered

a disgrace

to civilization, the sign of lower social strata, lesser races and

base animals.

According

to Freud the replacement of smell by sight as the dominant and superior

sense occurred at a stage in human evolution when "as a result of

our adopting an erect gate, we raised our organ of smell from the

ground". The adoption of an upright posture visibly exposed the vulnerability

of the human genitalia, necessitating the development of a protective

sense of shame associated with the emergence of an 'organic repression',

ultimately resulting in the foundation of the family unit and civilised

society. Freud associates the diminution of the olfactory sense with

the "cultural trend towards cleanliness" resulting in general feelings

of disgust directed towards bodily excreta. The residual coprophilic

instinctual components of the body are in turn derided by society

as perverse and incompatible with the norms of civilised 'human' behaviour

and the refinements of culture. But the instincts remain active, which

is why, still, "the excremental is all too intimately and inseparably

bound up with the sexual". Accordingly, Freud concludes that the net

effect of society's repression and sublimation of these bodily instincts

can be detected in a general lack of sexual satisfaction and in a

corresponding increased incidence of mental disorders and neurotic

illness.

Julia

Kristeva's celebration of ugliness as thematised in the writings of

Mikhail Bakhtin and Charles Baudelaire, signifies an eruption of the

sensual and erotic drives of the semiotic body in protest against

its repression on the part of the rational ego, which belongs to the

established order of the 'symbolic'. As such, the thematisation of

ugliness represents a direct assault on enlightened subjectivity's

horror of the unformed, its aversion in face of that which has escaped

the levelling, identitarian stamp of 'civilised' life. The aesthetics

of ugliness, therefore, reminds civilisation of a stage of development

prior to the rational individuation of the species in face of primordial

nature, the stage of its undifferentiated unity with nature, a moment

of 'weakness' and 'vulnerability' civilisation has attempted to repress

from memory. For civilisation is seized by an overwhelming fear of

relapse into that primordial, pre-individualised state against which

it struggled so concertedly to free itself that it has become tragically

incapable of releasing itself from the rigidification of the ego synonymous

with the principle of rational control. For in order to elevate itself

above the level of a merely natural existence and thus arrive at self-consciousness

as a species, humanity is required to subjugate its own inner nature,

that is, become attuned to the renunciation of the instinctual drives

of the semiotic body demanded by a 'reality principle' necessary for

the level of cooperation required for the conquest and subjugation

of external nature.

For

Kristeva, the 'pre-symbolic' realm of nature is synonymous with the

'pre-symbolic' semiotic space/time of the child's initial fusion with

and dependency upon the body of its m(other). The dialectic or process

of self-consciousness which enables self-identity (the same) to distinguish

itself from what is 'other', that is, the formation of subjective

and objective identity, necessitates the denial and repression of

this pre-symbolic state of fusion with the maternal body. The repression

of the maternal body in turn provides the foundations for the social

and symbolic mastery of nature, the body, of the non-identical, and

of the heterogeneous. According to Kristeva, "Fear of the archaic

mother proves essentially to be a fear of her generative power. It

is this power, dreaded, that patrilineal filiation is charged with

subduing". Yet, in the end, the rigidification of the ego required

for this purpose is ultimately so extreme that the original goal of

the process, the eventual pacification of the struggle for existence

and the attainment of a state of reconciliation with nature, is eventually

lost sight of; and the means to this end, the domination of nature,

is enthroned as an end in itself. For once the 'subject' comes to

perceive itself as absolute and its 'other', the maternal body of

nature, as merely the stuff of domination, this logic ultimately exacts

its revenge upon the 'subject', which has somehow forgotten that the

'other' is a moment internal to itself, in other words, that humanity,

too, is part of corporeal nature and is consequently a victim of its

own ruthless apparatus of control. A tragic dialectic ensues, whereupon

"Man's domination over himself, which grounds his selfhood, is almost

always the destruction of the subject in whose service it is undertaken;

for the substance which is dominated, suppressed and dissolved through

self-preservation is none other than that very life as a function

of which the achievements of self-preservation are defined; it is,

in fact, what is to be preserved".

Reason

abstracts, and seeks to comprehend through concepts and names. Abstraction,

which can grasp the concrete only insofar as it reduces it to identity,

also liquidates the otherness of the other. By making ugliness thematic,

the poetry of Charles Baudelaire gives a voice to those oppressed

and non-identical elements of society anathematised by the dominant

powers of social control that are commonly denied expression in the

extra-aesthetic world. Baudelaire's poems articulate the right of

the other, of the non-identical, to be. It accomplishes this task

by rejecting the burden of the concept and returning to the word's

forgotten, repressed meanings through the agency of metaphor. The

significance of ugliness, the tendency toward the incorporation of

increasingly ignoble, unrefined themes in art, in contrast to the

consistently more exalted concerns of classical art, is clearly expressed

in the title selected by Baudelaire for his major collection of poems,

Les Fleurs de mal.

The

notion that something ugly can be 'beautiful', that in fact in can

be beautiful precisely because it is ugly, tests the boundaries of

the permissible, opening up immense, previously untapped reservoirs

of experience. Poking fun at those painters who find nineteenth-century

dress excessively ugly, Baudelaire celebrates the black frock-coat

and dress-coat as "the necessary costume of our time" expressing the

intimate relationship of modernity with death: "The dress-coat and

frock-coat not only possess their political beauty, which is an expression

of universal equality, but also their poetic beauty, which is an expression

of the public soul - an immense cortege of undertaker's mutes (mutes

in love, political mutes, bourgeois mutes). We are each of us celebrating

some funeral".

Baudelaire

cites the example of the artist Constantin Guys, a spectator and collector

of modern life's curiosities: "this solitary, gifted with an active

imagination, ceaselessly journeying across the great human desert

- the last to linger wherever there is a glow of light, an echo of

poetry, a quiver of life or a chord of music; wherever a passion can

pose before him, wherever natural man and conventional man display

themselves in a strange beauty, wherever the sun lights up the swift

joys of the depraved animal". Julia

Kristeva shares Charles Baudelaire's fascination with the combined

figures of the dandy and the flaneur, the artist and the poet,

keenly receptive and perfectly at home in the streets, drifting through

the crowded boulevards, painting in colours and in words the sensory

array and variegated experiences of modern life. The artist adrift,

acutely sensitive to the sadness of loss and the inevitably of decay

captured in the fading and fragile beauty of each fleeting moment;

a sadness reflected in the momentary glance of every stranger briefly

encountered while passing through the city's crowded streets. The

wandering poet whose

artistic creations disrupt the fossilised social conventions of the

symbolic order by resurrecting through the colour and play of words

the memory of the semiotic experience: a feeling of bliss and unity,

an ecstatic dissolution of the boundaries and divisions that separate,

a sensation of 'oceanic' oneness; feelings and sensations synonymous

with that original state of fusion of the infant's body with the body

of its mother. The restoration of a 'love' experienced as the extinction

of otherness; a love that the art of poetry articulates through the

agency of 'metaphor', or the 'marriage' of one object with another;

an analogical mode of thinking defined by the poet Stephane Mallarme

as the secret to the 'mystery' of poetic creation: "Herein lies the

whole mystery: to pair things off and establish secret identities

that gnaw at objects and wear them away in the name of a central purity".

The

flaneur or dandy, immersed in the flux of each passing moment,

produce themselves as objects of a continual aesthetic elaboration

whereby their passions, their behaviours, and their very lives, become

works of art in perpetual progress of formation. Charles Baudelaire,

poet and dandy, exemplifies for Kristeva her notion of the 'subject-in-process',

with "flowing locks, pink gloves, coloured nails as well as hair",

who produces himself through the very act of writing his poetry. Poetry

that dissolves and then merges objects together again into one harmonious

unity of the senses: a 'synaesthesia' of the senses consisting in

the disintegrated displacement and reassembled condensation of sensations

fused together into a unity; a process amounting to the poetic re-enchantment

of the everyday, familiar world. Poetry that evokes for Kristeva "that

archaic universe, preceding sight, where what takes place is the conveyance

of the most opaque lovers' indefinite identities, together with the

chilliest words: 'There are strong perfumes for which all matter is

porous. They seem to penetrate glass'".

Mikhail

Bakhtin traces the historical process by which images of fundamental

bodily processes like "eating, drinking, copulation, defecation, almost

entirely lost their regenerating power and were transformed into 'vulgarities'".

Thus a hierarchy is established between the high and the low, the

official and the popular, the classical and the grotesque, the top

and the bottom, the face and the body's nether regions. Bakhtin celebrates

the festivities of the carnival and the antics of the carnivalesque

as the symbolic inversion and cultural negation of traditional distinctions

between the 'high' and the 'low', leading to the negation and inversion

of established social and political cultural codes and norms.

The

grotesque body of the carnival is the corporeal body of the multitude,

associated with the 'low' and the base, with orifices that leak and

drip, with impurity, disproportion, immediacy, and with the porousness

and indeterminacy of abject materiality. This is the material body,

the direct antithesis to the classically beautiful, ideal body, which

is culturally defined as symmetrical, elevated, and refined. An ideal

body conceptualised as a sealed, self-contained vessel, with a protective

shell, or shield, serving to conceal (and deny) its material, corporeal

aspect. A bodily ideal verging on the spiritual, symbolising a set

of ordered and hierarchical relations serving to maintain secure and

impervious boundaries separating vital distinctions between such designated

terms as inside and outside, proper and improper, order and disorder,

ugliness and beauty, the corporeal and the spiritual.

In

contrast, Bakhtin and Kristeva celebrate the grotesque, lower bodily

stratum, expressed in the antics of the clown and the frivolity of

the circus, and in the folk imagery contained in Rabelais' joyful

descriptions of the medieval carnival. Images of bodily satisfaction

and sensual gratification preserved within the oral language traditions

and festivities of the common people, and recorded in historical texts

concerning antique satyric drama and ancient practices such as the

Roman Saturnalia. A history that represents for Bakhtin and Kristeva the material principle of the body's resurrection as the location

and promise of a utopian

alternative. The 'primary processes', subterranean drives, rhythmic

pulsions, and libidinal connections of the semiotic body continuously

irrupting, subverting, destabilising, and threatening the rigidities

and stases of a sociosymbolic order that in turn endeavours to recuperate

and contain these potentially destabilising affects by incorporating

them into its very structure, in what can only be described as a dialectical

conflict and provisional unity of opposites.

For

Julia Kristeva "The semiotic (body) is articulated by flow and energy

transfers, the cutting up of the corporeal and social continuum as

well as its ordering in a pulsating chora, in a rhythmic but

nonexpressive totality". Mikhail Bakhtin's image of the grotesque

body is Kristeva's semiotic body, the earthly element of the maternal

womb, epitomising the cycles of life, death, and renewal, terror and